Dick Negus’s contribution to: ‘Ernest Hoch remembered by his friends. The importance of Ernest’, Designer, September 1985 (London: Society of Typographic Designers) pp. 20–21.

Ernest Hoch’s death has robbed the typographic world of its fountain of logic and the Society of a distinguished past vice-president. Ernest was an immensely dedicated man. He brought, to everything he did, a tireless strength of purpose that was at odds with physical size. He was a giant in a frail body.

His academic background was unusual in that he studied chemistry before attending the Graphische Lehr-und Vesuchanstalt in Vienna. He came to England in 1938 and during the early years of the war he suffered internment, then became a laboratory assistant. Nineteen forty-five saw him in an advertising agency, but he found this work shallow for his talents and by 1948 he had started his own design company.

During the fifties and sixties he held a number of part time lectureships and in 1969 became Principal of Coventry College of Art and Design (later Dean of Faculty, Lanchester Polytechnic). He was appointed part time Reader at Reading University in 1971 and it is the work he carried out there until 1980 for which he will be best remembered.

He was one of a small, but highly influential group of continental designers who settled here after fleeing Hitler’s Third Reich. It may be difficult for many younger members to comprehend the importance of this group and of Ernest’s own part in it, unless they had the privilege of working with him or being taught by him.

I did have that privilege. Ernest and I worked together on a number of occasions and each was an electric experience. I particularly remember a small working party of the SIAD whose job it was to restructure the Society. Rather like the advertisement for batteries, where only one was left with power, it was Ernest who was still working until the early hours night after night – making radical decisions with the same cool logic as he did with minutiae.

Ernest was also the first to see the potentials and also problems associated with computer typesetting. He campaigned for aesthetics to be brought to bear before vested interests closed ranks. But the industry was short sighted and the results dogged the path of computer setting during its early years. Characteristically Ernest never bore a grudge and energetically joined in the rescue operation.

It is commonly assumed that those endowed with wisdom lack the common touch; that high intelligence eschews humanity. There is hardly a better denial of this than in the life of Ernest Hoch. He was charming and self-effacing; generous and patient to students when it came to passing on his hard earned knowledge; the kindest husband to his wife Ruth and a very dear friend to many.

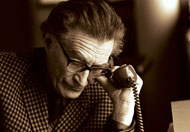

Ernest Hoch. Photo: Richard Southall